Eighteen months after my very first attempt at running, I ran a half-marathon. I finished with a time of 1:40:35. That’s pretty fast, especially for a beginner, but I wanted to get faster. I didn’t want to be “fast for a beginner.” I wanted to win races. At the rate I was improving, it was possible.

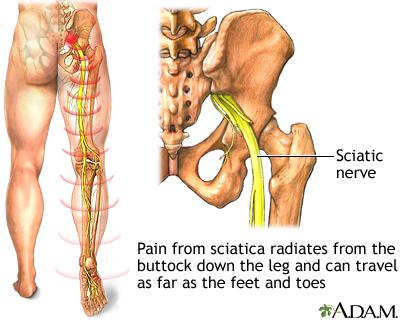

Leading up to the half-marathon, I trained through some hip pain. It lingered after the race, and several months later, the pain travelled down my right leg and into my calf. It was sciatica, which is a four-syllable catch-all term for serious pain in the ass (and leg). The sciatic nerve has roots in the two lowest lumbar vertebrae and the uppermost sacral vertebrae, and it threads through the pelvis and piriformis (a deep hip rotator) and runs all the way down the leg. Somewhere along its path it was being compressed and irritated. One morning, I had to do the unthinkable: stop in the middle of a run. That led to a year of chiropractic appointments, physical therapy, massage therapy, and conductive nerve studies.

I didn’t get better with treatment. I went to two different chiropractors, a sports medicine physician, two physical therapists, a hip specialist, and a nerve pain specialist. Running became a dreaded chore. But I ran anyways. I was like those racehorses who break their legs on the track and keep running until they finish. I was compelled to run. I felt like I had to. Six minutes in, I would find myself limping, swinging my bad leg around my hip instead of driving it forward and through. I had to stop and stretch every five minutes just to make it through three-mile jogs.

An MRI finally diagnosed me with a labral tear and femoralacetabular hip impingement: the top of my femur was misshapen and had torn the cushioning cartilage in my hip. The sciatica was an accessory to the crime rather than the culprit, and probably came from me compromising my stride to protect the damaged joint. Trying to run through the pain had made a bad problem worse. The doctor gently told me I needed surgery and would need to stop running completely.

I was devastated. For months after the decree to stop running, I’d burst into tears every time a runner glided past. My running career had just gotten started. I’d barely begun to tap my potential. It wasn’t fair.

After the surgery, I never fully healed. I could run, but I couldn’t run the way competitive distance running requires. I officially gave up. I tried a brief stint of cycling, but I hated the stupid coordinated outfits, and those knee-length shorts aren’t flattering on anybody, especially me. I tried swimming, but I was terrible. One lap left me gasping for air like a trout. I was so bad that a swim coach approached me while I was choking through a breaststroke and gave me a free lesson.

Then I decided to try yoga. Seriously try. I’d practiced off and on at home and taken the occasional studio class for years, but I’d never dedicated myself to a practice. Then I found Ashtanga. It was challenging, both physically and mentally, and it required dedication. I needed something in my life that required dedication.

I came out of that first class feeling two inches taller. Three weeks later, I was practicing Ashtanga six days a week. The chronic pain in my hip and thigh started to melt. Three months later, I could run without the familiar ache running down my leg, but I barely cared.

Ashtanga had replaced running. It features many of the aspects of running I loved so much: the challenge, the moving meditation, the routine. But it leaves me in touch with my body in a way I never was before I found a regular, traditional yoga practice.

Athletes are encouraged to push—to find better, faster, stronger. We wear t-shirts that say things like, “pain is weakness leaving the body.”

In my case, pain was telling my body that it was being damaged to the point that it required surgery. When I was running, I didn’t know the difference between pain and discomfort. It was all one big gray blob of yuck. Now, I can tell when I’ve stretched or flexed to the point of damage. I can evaluate discomfort and stop what I’m doing before discomfort changes into pain. It took working one-on-one with an instructor, memorizing a sequence, and making it routine to reach this level of awareness.

Yoga enthusiasts are famous for claiming that yoga is the answer to everything. I’m trying not to go down that path. Yoga isn’t a panacea. But it can be the key to a door of better body-mind connection, something that athletes at the top of their game consistently seek.

Today, I teach Yoga for Athletes, and I teach them a modified Ashtanga sequence. I show them how to connect with their breath. I encourage them to play with their edge, finding it and then backing off. I have them lengthen as well as strengthen their muscles. And hopefully, they’ll take what they learn in the yoga room to the field, the court, the track, or the weight room.

I don’t expect my students to drop their sport of choice and become Ashtangis. I don’t want them to. I want to help them find the awareness they need to keep doing the physical activity they love. I don’t want them to push themselves into a hip surgery at age 26 like I did. They don’t have to. No one does.

Pingback: Scott Spitz starts fundraiser, practices yoga

Pingback: Leave Kino’s Hip Alone | The Buddhi Blog