Yoga wasn’t always an array of beautiful white bodies in expensive clothes with limbs that bend into complicated poses. It has a muddled history that began in a decisively brown-skinned world before its appropriation by westerners and eventual viral spread throughout the western world.Possible evidence of yogic practices was found as early as 2500 BCE in the form of a seal featuring what some consider to be a prototype of Lord Shiva in a yoga pose, and textual references to yoga began to appear around 300 BCE, but they described a moral and philosophical practice instead of the physical postures that are so pervasive on Instagram and YouTube. Hatha Yoga, the first arm of yoga to include those physical postures, didn’t manifest until the 1400’s and is chronicled in detail in the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, one of the better-known classical texts on yoga.

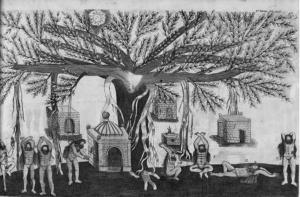

Beginning in the seventeenth century, documentation of Indian yogis began to make regular appearances in Western travel writing. These practitioners contorted their bodies into strange positions, sometimes for hours at a time, and lived rigidly ascetic, often antisocial lives. They wandered around in the nude, covered with ashes made by burning cow dung. Sometimes, they padlocked themselves into drapes of heavy chains, turning the act of standing up and walking into a feat of physical effort. They slept on beds of nails. They ate only ghee, a clarified butter, and certain vegetables. European colonials were more likely to identify practitioners of Hatha Yoga “…with black magic, perverse sexuality, and alimentary impurity than with ‘yoga’ in any conventional sense,” according to Singleton.

Interestingly, these European accounts state that western visitors aren’t the only ones perturbed by the yogic practices. A 1698 travelogue by John Fryer notes that fakirs, another group of vagabond holy men that are conflated with and are indeed similar to the yogis of this time period, “are the Pest of the Nation they live in.” Both yogis and fakirs often used their extreme physical practices as exhibitions to achieve their livelihood. These practices, such as “overgrown nails that pierce the flesh of the hand, dislocated arms, and excruciating postures held for so long that the limbs in question become ossified and shriveled,” inspired a perverse fascination in onlookers both native and western that must have made exhibitionism a natural means of financing their daily lives. Fryer also noted that they inspired fear in Indian citizens through their aggressive begging. Another branch of pre-modern yogis devoted themselves to fighting, and became militant and organized sellswords that were eventually outlawed by the British because of the threat they posed to the East India Company.

In a precapitalist economy that most closely resembles what Karl Marx would call feudalism, the yogis and fakirs were outsiders. History of Indian Economic Thought, by Ajit Dasgupta, says “exemption from the tax was granted to…hermits and mendicants generally.” The tax referred to was a tribute paid in exchange for protection and security, and has religious roots in Islam as well as a totalitarian monarchy in which “the government was not merely tax-gatherer but also agriculturalist, cowherd, road-builder, cattle-breeder, miner, forester, manufacturer and merchant.” Postural yoga in its earliest recognizable iterations existed outside of both social and economic norms and continued in that vein for centuries.

The Victorian era and its revulsion for the body permeated popular conceptions of yoga as well. S.C. Vasu, a major figure in the portrayal of Hinduism to English-speaking cultures, attempts to reclaim yoga from “grotesque beggar-figures” and “sinister holy men” by renouncing their physical practices and even censoring descriptions of them from his late-nineteenth century translations of important Hindu texts. For example, the practice of vajroli and amaroli are left out entirely. These are, respectively, the reabsorption of vaginal and seminal fluids back into the penis and the oral consumption of urine. According to Singleton, “Vasu is attempting…a reclamation of the very signifiers ‘Yogi’ and ‘Yoga’ from what they do mean in popular parlance to what they should mean.” There is a distinct separation from the physical body in the yoga that Vasu and other proponents of Indian theology discuss. The body isn’t ignored entirely, but it is relegated to a scientific specimen, which is perhaps echoic of the Enlightenment period that preceded these writings.

Swami Vivekananda, a late nineteenth-century Hindu monk, famously introduced Hinduism at the Parliament of the World’s Religions, an event coinciding with the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893. He is credited with reviving yoga from its dangerous outsider status. He claims that “the chief aim and result of hatha yoga—‘to make men live long’ and endow them with perfect heath—is an inferior goal for the seeker after spiritual attainment.” He demotes the breathing and postural exercises described in the Hatha Yoga Pradipika to lesser expressions of yoga, and he expresses this demotion in lectures throughout India, England, and the United States. Vivekananda is joined by the German Orientalist Max Müller in popularizing this concept that succeeded in the work that S.C. Vasu also began—reclamation of the signifiers yoga and yogi. No longer did yogi mean a morally suspect contortionist, and the spiritual, transcendent component of yoga was established as its chief building block.

Concurrently, the physical body began to rise in stature in other spheres. The first bodybuilding displays and the inaugural modern Olympics occurred in the 1890’s. These were hallmarks of a world fascinated by the human body, and India was not exempt from this influence thanks to their colonization by the British. The first YMCA was founded in London in 1844 as a refuge from the squalor and depravity of the city, and the first YMCA’s with gymnasiums were constructed in 1869. Having a fit body became part of overall wholesome living, and if not a path to spiritual enlightenment was certainly a path to moral fortitude and general human growth.

Today, going to the YMCA is synonymous with going to the gym, showing how thoroughly the Y’s initial impulse of self-improvement morphed into physical self-improvement as a means to that end. The Indian YMCA translated this impulse into “education through the body, not of the body,” as Singleton says. The body was used as a tool to access other parts of the self instead of simply being the end-goal, returning full circle to the ideology behind the medieval and Enlightenment-period Hatha Yoga. Between 1900 and 1930, the YMCA’s popularity in India soared. Its discourse “was intended to contribute to the even development of the three-fold nature of man—mind, body, and spirit…in the hands of the YMCA, physical culture was eventually elevated to a position of moral and social responsibility.” That mind-body-spirit complex is a mainstay of contemporary yoga, but it is often misattributed to ancient yogic texts instead of the YMCA. The Y in India may actually be largely responsible for the inclusion of asana practice into a physical fitness regime, as YMCA staff in India made sure to include “attractive indigenous activities” into their programs.

The poverty in late nineteenth and early twentieth century India rivaled the squalor of Dickensian London, recreating the situation that caused the initial founding of the YMCA. However, the extreme poverty was not the result of industrialization, as it was in England, but as a result of an economy that relied too heavily on agriculture and was thus prone to ravaging famine. Some Indian economists welcomed foreign interference because colonization brought diversification to an incredibly non-diverse economy that still relied on farming villages as its primary means of production. The reason behind India’s slow industrialization may lie with cultural principles that discourage the accumulation of wealth. Entrepreneurship was not a common Indian trait, but subservience to a religious prescription of labor was. Perhaps because of this, native Indians were viewed by the Brits as inherently inferior, even effeminate, and fell victim to the colonial subject’s inferiority complex. Since physical exercise was viewed by India’s colonial power as a means to transcending an abject state, the subjects began to integrate it into their own culture. By 1930, India was a “hotspot” of physical education.

T. Krishnamacharya, the godfather of modern yoga, in an asana similar to the proto-Shiva seal. Photo credit: yoganirvana.com

In the midst of this hotspot, Krishnamacharya, the godfather of contemporary yoga, rose to prominence in the South Indian city of Mysore. Krishnamacharya was teacher to the most prominent yoga gurus in history: Pattabhi Jois, B.K.S. Iyengar, T.K.V. Desikachar, and Indra Devi. Krishnamacharya was sponsored by local royalty in South India, and his knowledge was supposedly garnered from a yogi who lived in solitude in a cave in the Himalayas and the Yoga Korunta, an ancient text that was conveniently partially destroyed by ants. He developed hundreds of asanas, as well as meditation and pranayama, or breathing techniques, and taught them to these pupils in distinct ways. Between the 1930’s and the 1950’s, his legacy was solidified through his teaching and demonstrating program in Mysore, and initially projected to the western world by Indra Devi, nee Eugenie Peterson.

Devi became a student of Krishnamacharya through her parents, who were friends with the Mysore royalty. In the late 1940’s, she opened a yoga studio in Hollywood, and became teacher to the stars. Over the next few decades, she spread the gospel of a yoga accessible to westerners and toured the globe dressed in a traditional Indian sari. The yoga that Devi promoted was more similar to the YMCA’s wholesome healthy lifestyle than it was to ascetic mendicants. She established the first yoga studio in Hollywood and was discovered by cosmetology expert and entrepreneur Elizabeth Arden, who “soon became a follower and advocate of Indra Devi’s yoga methods, incorporating them in her upscale health spa programs,” according to an article written after Devi’s death in 2002. Yoga became accessible to the United States through the top rungs of the socioeconomic ladder.

In the 1950’s, Devi wrote Forever Young, Forever Healthy and taught movie stars like Jennifer Jones, Marilyn Monroe, Gloria Swanson, and Greta Garbo. America’s love affair with media celebrities and everything they did solidified yoga’s reputation as desirable and thus commodifiable. Stephanie Syman, yoga instructor and author of The Subtle Body: the Story of Yoga in America, says “Reading Forever Young, Forever Healthy, you could imagine taking one of Devi’s classes, powdering your nose, then lunching at the Brown Derby. She [Devi] reduced yoga…down to something that fit more readily into American ways of thinking. Yoga was in effect a health tonic.” A health tonic is something that can be bought and owned. Once purchased, it is expected to bring results, and often does, thanks to the self-fulfilling prophecy of the placebo effect.

I’m unsure of the legitimacy of these poses combined as a poster, but they were supposedly sent out as a promotional set in 1948. Marilyn did appear in LIFE magazine in yoga asanas during that era. Image credit: grimmly2007.blogspot.com/

Meanwhile, the flower child movement of the 1960’s and 1970’s produced a generation of young adults who were seeking enlightenment through drugs, eastern religion, and free love. Some of these seekers wound up in South India, under the tutelage of Krishnamacharya’s disciples. When enough of these seekers found benefit in their study of yoga, they began bringing their gurus to the United States. By the 1980’s, fitness was the new buzzword of contemporary culture, and yoga asana practice complemented the body-obsession of this decade in America just as it complemented the growth of the YMCA in late imperialist India. By the 1990’s yoga studios had popped up in many western cities, and by 2012, nine percent of American adults—20.4 million people—practiced yoga according to a study by Yoga Journal.

Six hundred years after the writing of the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, Yoga Journal is the western authority on Hatha Yoga. It’s a glossy magazine with a total readership of over 1.96 million, as reported on its Advertise With Us page. The median household income of Yoga Journal readers is $84,120, and 38% of those readers have an annual household income over $100,000. Most gyms now feature yoga classes, and even small midwestern towns like Madison, Indiana (population 12,083) have yoga studios. Practicing yoga today includes paying fifteen to twenty dollars per class, purchasing a polyvinyl chloride or thermoplastic elastomer mat with a price tag that can rise as high as $150, and buying yoga-specific workout clothes, which can cost over $100 for a single outfit. “Yoga-lebrities” such as Kino MacGregor and Seane Corn travel the world to teach at conferences, sell their own personal brand of yoga accessories and clothing, and receive press from Oprah, the queen of media. A yoga studio parking lot is usually filled with BMW’s, Mercedes Benzes, and SUV’s. The yogi of today can also travel to exotic international locations to pursue her enlightenment—for the reasonable price of $2,195.

The lovely Rachel Brathen AKA @yoga_girl. Her inspirational messages appear regularly on Instagram. Image credit: Elephant Journal

The history of yoga as it appears today is convoluted, complex, and intricately related to international perspectives on the body and economics. It is important to remember that the lives of the wandering yogis of the fifteenth century are no more inherently authentic than the lives of yogis practicing in contemporary western society. But it must be recognized that yoga has been commodified in spectacular fashion and turned into something very different from its roots. Maybe what exists today in yoga studios is the yoga that fits the world today. I can’t presume to know. All I can do is listen to Guruji also known as Sri K. Pattabhi Jois and the father of Ashtanga yoga and trust that “Practice…and all is coming.”

Sources:

Aboy, Adriana, “Indra Devi’s Legacy,” Hinduism Today, October/November/December 2002

Dasgupta, Ajit K., History of Indian Economic Thought, Routledge, 1993. Florence, KY. P 45

Desai, Gita, Mukesh Desai, Sujay Desai, Ajay Mehta, Georg Feuerstein, Patricia Walden, Dean Ornish, Mehmet Öz, Āśita Deśāī, and Michael Karp. 2004. Yoga unveiled. [United States]: Gita Desai.

McRae, John R. (1991). “Oriental Verities on the American Frontier: The 1893 World’s Parliament of Religions and the Thought of Masao Abe”. Buddhist-Christian Studies (University of Hawai’i Press) 11: 7–36.

Singleton, Mark. Yoga Body: the Origins of Modern Posture Practice. Oxford University Press, 2010

Syman, Stephanie, The Subtle Body: the Story of Yoga in America, New York, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux , 2010, p 191-197

Unknown author, “History of the YMCA,” http://www.ymca.net/history/1800-1860s.html

Yoga Journal, “Yoga in America,” www.yogajournal.com/press/yoga_in_america

Yoga Journal, “Advertise with us,” http://www.yogajournal.com/advertise/

Yogi Swatmarama, Hatha Yoga Pradipika, trans. Pancham Sinh, (Creative Commons: 1914), https://ia600401.us.archive.org/35/items/HathaYogaPradipika-SanskritTextWithEnglishTranslatlionAndNotes/HathaYogaPradipika-SanskritTextWithEnglishTranslatlionAndNotes.pdf.

Love yoga. Its philosophy and lineage. Through to our times though, very interesting..

Agreed! Thanks so much for reading.